|

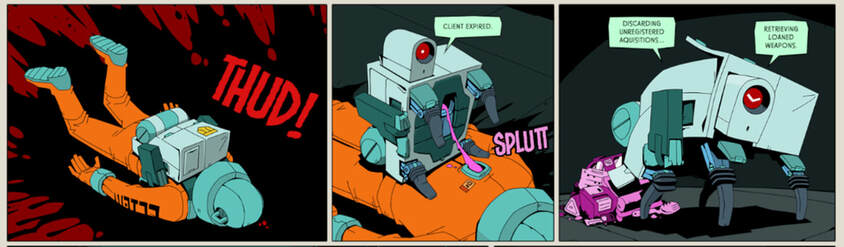

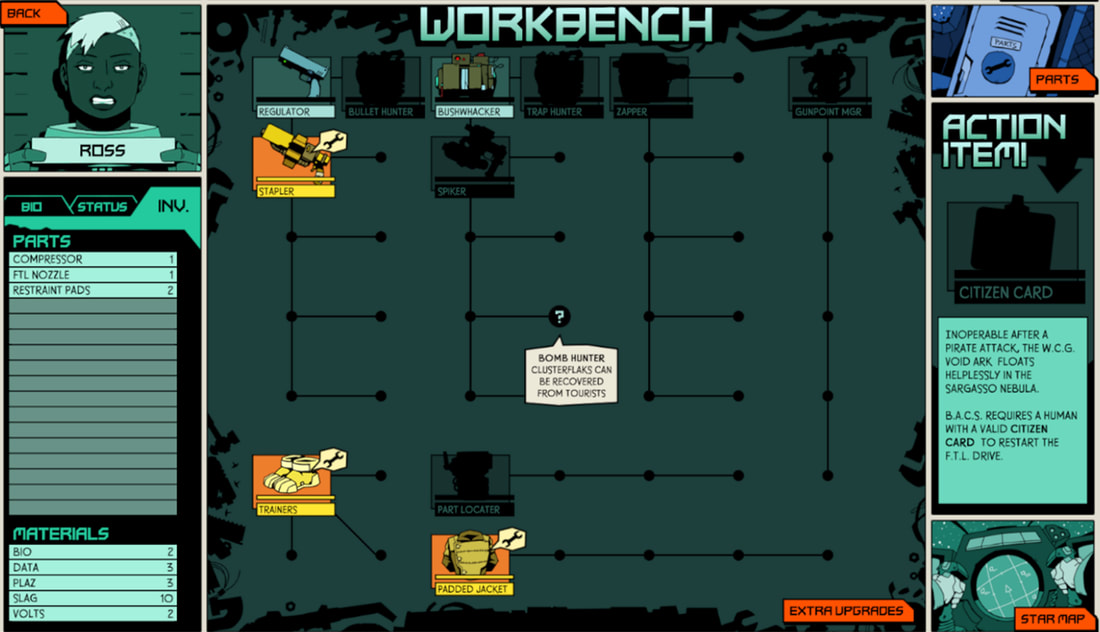

This is something I’ve wanted to do for a while now. It’s a game review (skip to the image of the game title if my preamble doesn’t interest you). I realize my branding of this blog isn’t exactly consistent. Am I giving advice? Am I journaling out loud? Am I discussing the experience of being an audiobook narrator? A voice actor? An actor in general? A businessperson? A person in general? Am I suddenly changing careers and starting from square one in independent media criticism (no, definitely not that one)? What exactly am I doing here? Well, first of all: Indulging an age-old passion of mine. I’ve always loved discussing games as an art form and critiques thereof, and it’s my blog, so why not? Second, I think if I had to describe what my aim is in writing these seemingly disparate posts, I think would be this: I want to transcribe anything that I, as any of the aforementioned professions/states of existence, find generally useful in my pursuit of bettering those things. And I’ve become really obsessed with the idea of healthy recreation lately, and there’s a very important reason for this. I have an addictive personality. I have never had a drop of alcohol nor experimented with any mind-altering substance not out of any moral opposition to these things but simply because I know how my brain is wired. Yes, there are those who would correctly state that things like family history, genetic predisposition, and data gathered from observations of my own tendencies toward addictive behavior are not necessarily a guarantee that partaking of these things will go badly for me, but I see it as rolling a pair of loaded dice. Yes, there’s a chance I could roll the game-winning double six (I don’t know a lot about dice games, so I’m just making up rules), which is already unlikely, but the dice are also weighted not to roll a six. If we’re being completely honest, there’s a nonzero chance of winning this game. But given the stakes and the odds, I choose not to play. That’s it. If you can enjoy these things in healthy moderation, fantastic. I’m happy for you. Truly. But… For someone like me, I’ve had to learn to be very careful about how I enjoy myself. The parts of my brain that demand a quick fix are really active and borderline insatiable, and the fact that I spent the vast majority of my childhood wolfing down terrifying amounts of sugar and carbs while video gaming away so many hours of my life I ended up neglecting most other aspects of it is including school, romance, friends, maturity-inducing introspection, community involvement, and family, is a testament to that. At that time in my life, I wasn’t sure about a whole lot, so maybe it could be argued that I, a kid, was, as some kids do, seeking certainty and comfort, and I found that those things when I was reminding myself that yes, indeed, sugar and carbs taste nice, often while wielding absolute power over some sort of virtual space empire or another (maybe an ancient Roman empire if I was feeling academic), which, come to find out, is a remarkably convincing simulacrum of existential agency. But I think, especially given recent developments in the game world, like the controversies surrounding the introduction of Totally-Not-Gambling-on-Fundamentally-Meaningless-Digital-Paraphernalia-With-Actual-Money-to-a-Genuinely-Horrifying-DegreeTM to forms of entertainment ostensibly meant for children, it’s worth considering some potentially uncomfortable ideas about the standards by which we value our entertainment. So I ask: Why is “addicting” a good thing?! That descriptor comes with warning labels for most everything that isn’t a video game/sugary foodstuff. Legislative wars have been fought to draw attention to the effects of substances like nicotine (and before any fellow game lovers that might be among my as yet minuscule readership dive for the comment section to tell me games aren’t drugs: I know. I get it. I’m not looking to be the next cynically motivated alarmist here; I’m simply calling into question our weirdly inconsistent valuation of a word). Whole groups have formed to combat the addictive effects of gambling, or narcotics, or alcohol. But suddenly, when we’re perusing reviews and comments for our next game, we’re actively looking for sentiments like “I can’t stop playing” or “This kept me up until 5AM 3 nights in a row” or “Trapped in digital rapture. Send help. Or don’t; I kind of like it here. Work can wait.” I was among those that would consider these indications of an apparent dopamine drip that keeps on giving hallmarks of excellent game design. But seriously. Why?! I can’t speak for every one of those reviewers or players, but I can guarantee that, were any of those comments left by me, they would immediately be followed up in my real life with “why the hell did I do that?!” or “Why can’t I stop playing?!” or “Oh s**t I actually needed that time I spent chasing the dragon to work on my actual life which will now be appreciably more stressful for several long, painful days while I catch up on what I would have otherwise had time for had I not done that” or “well there go those healthy sleep habits that were tangibly improving every aspect of my life that I was working on.” The more I think about this design ideal, the more I realize that it’s a dopamine drip that keeps on taking, at least for me. Maybe a differently wired brain that isn’t susceptible to repeated overindulgence would have no idea what I’m talking about, but wouldn’t a game that demands you keep playing and playing and playing and playing until your recreation time becomes a new source of stress actually be a game designed to be un-satisfying? Food is eventually supposed to make you feel full, right? And the varieties that don’t are the really sugary ones that set off the same pathways cocaine does and ultimately harm you if you keep indulging in them, right? And sure, there’s always the question of personal agency involved, but the longer I live, and the more I think about and listen to experts on this topic, the more it seems like agency is best exercised manipulating one’s environment to pre-empt problematic stimuli (for example, hiding the cookies and moving the veggies to a readily visible place in the fridge) rather than calling upon what increasingly appear to be apocryphal willpower reserves in the hopes of going Life Coach Super Saiyan and “just stopping” or “just doing it.” So this would mean that, in order to indulge in a medium I enjoy healthily, I would essentially need to prominently display the…dear god, I am not calling this segment “the Vegetables of Video games.” One, that’s not really an apt comparison anyway; I don’t think vegetables are a universal symbol of recreation, two, I might review more than just virtual entertainment at some point in the future, and three, that title is probably the surest way to convince myself and anyone else not to try out what I’m going to discuss here. So, instead of attempting to come up with a catchy title (a mildly unsatisfying and possibly temporary excuse for which you probably already read when you read this post’s title), allow me to explain the sort of game I’ve come to really value, and what you can hopefully expect from both these semi-regular reviews and the games I discuss within them. 1. The gameplay loop must be satisfying. That is to say that, after a while, I want to stop playing. I have had my fill. The more I learn to healthily recreate with my activities of choice, the more I realize that a sort of built-in timer that leaves my brain going “cool; I’m good now” is a strength. It’s inherently conducive to work-life balance. Yes, there are plenty of great games that possess the mythical “just one more turn” quality. You’re (hopefully) not going to find those here. Frankly, as much as I used to love playing such titles on the regular, I just don’t have the time for them, or the associated smackdown with my brain’s busted reward centers that inevitably accompanies my playing them anymore. 2. Said loop must complete inside of an hour (give or take a small grace period). The point of these titles is that they feel like a complete experience that doesn’t eat a lot of time. 3. They’re probably all going to be games I really like. Most likely, I will, of course, not love anything and everything about them, and I hope that I’ll be able to give you a clear enough picture of what exactly the experience of playing them is like that you’ll be able to judge whether they’d be fun for you. But on the whole you should expect the sentiments expressed towards games discussed herein to be positive. I’m not working for any publication, which means I have complete control over the titles I play. I’m also probably going to be taking several of my actual breaks by playing these titles to help me write these reviews. Which begs the question “Why would I torture myself with stuff I hate?” 4. I’m going to break these into two segments. First I’ll discuss the overall feel of the game, including what I like about it, what I don’t like about it, the gameplay mechanics, the aesthetic, the general “vibe (and stuff)” for lack of a better word an actual games critic might know, and so on to help you judge whether or not this is something you might enjoy. Second, I’ll discuss what makes this uniquely suitable to someone with a busy schedule and/or tendency towards overindulgence. What about this game is satisfying? How long does it take to get that feeling of “I’m good” that we too often malign as “getting bored?” What gameplay mechanics do I think contribute to the satisfying nature of the gameplay loop? 5. These are most assuredly not going to be timely. If you’re looking for reviews of the latest and greatest, don’t look here. I’m hoping the value of this segment will come primarily from the way I’m going to discuss these games as outlined in the previous point. 6. I’m not going to give numerical scores, because, like I said, anything I discuss here, I already like, so I’d be operating in the 7-10 scale not due to fear of reprisal for uttering a word of disfavor, but rather because that’s actually how I feel about everything here. So even if I liked the idea of attempting to force quantitative measures of quality on the most subjective elements of the already subjective, it would just be redundant. I will, however, give a TL;DR at the end consisting of a quick, bottom line summary, as well as two categories: “For the Weekday” and “For the Weekend,” as these games may not be on the whole suitable for someone especially prone to the “must keep playing” mentality. Maybe certain game modes are great for a quick break, and others are best left alone unless you plan on spending an actual, honest day off on an extended play session (nothing wrong with that, of course; but I think we’ve all been through the pain and stress of the domino effect of a day off we didn’t properly plan for). Anyway, preamble done. Hello, if you’re a new reader (and if you’re from the future, one I hope is inching ever closer to cyborgs and spaceships, and you’ve been linked back to this explanation by a future article because you’ve never read one of these before, you may now return to whatever review you were reading), hello again and thank you for your recurring readership If you aren’t, and to audiences new and old, I hope you enjoy! OK! So, if you read the long-winded “why” of this whole thing, thanks! Hope it fulfills its purpose! If you didn’t, I still hope you get something out of it. Today's Selection: Void Bastards!Part 1: The GameVoid Bastards is, without a doubt, one of the most stunningly beautiful games I have ever laid eyes on. There is a reason players and reviewers alike liken it to a comic book come to life. It is one. From panel one, I was immersed in its world, and taken by its thoroughly British dystopian cynicism. This a world of brutal corporate indifference, thoroughly stratified, despotically administrated, unapologetically bleak, and absolutely hilarious for it. Rather than opting for the sad tale of a lonely, lost spacefarer scavenging spaceships in a desperate bid to survive a la Out There (its own brand of beautiful for sure, but a decidedly melancholy one), Void Bastards is a source of narrative pleasures as masochistic as they are sadistic. It is as much an exercise in enjoying the pain this game inflicts upon you as a member of its world as it is in delighting in the suffering of its inhabitants. As I played, I was both fascinated with what fresh, senseless hell I was going to be coerced into enduring in the name of running increasingly stupid errands for an AI trying, failing, and utterly not caring that it is failing to motivate me with boilerplate corporate cheerleading, but I was also taking a twisted pleasure in watching just how deep the comically cruel corporatism of this world ran. It was a decidedly bizarre, morbid joy that only got more delightfully sick with every turn of the comic cutscene page. But of course, it might help to know what exactly this game is even about and how it plays to understand why I love it so much, and why you hopefully will too. So: You play as a prisoner, or “client” in true euphemistic re-branding of the awful fashion, aboard the Void Ark, a vessel carrying one million passengers charged with offenses that range from severe enough to understandably warrant some form of reprisal (like “detonation of an explosive device in a public area”), to the unsettlingly petty given their punishment (such as “failure to pay cafeteria bill”) to the completely bonkers (“breaking warranty on mobile phone” comes to mind). All are equal in the eyes of the mega-conglomerates that rule the stars. All must be subject to “dehydration.” Yes, clients are stored for transit by being desiccated into powder and sealed away in packets. To revive, just add water! Boom, instant gofer for BACS, the impeccably voice acted artificial intelligence determined to navigate the Ark through the Sargasso Nebula, the spaceborne fogbank of derelict vessels, ruthless pirates, gargantuan space monsters, and mutant horrors in which the ship has somehow gotten lost. Your goal? Hop from vessel to vessel salvaging whatever random crap BACS asks for, knowing full well that everything you do is in service to the greater objective of escaping the nebula and seeking safe harbor in…space prison. And if you die, perhaps impaled on the spiky growths fired from the hulking, twisted form of what was once a security guard, or blasted to paste by the detonation of one of the many fedora-clad slug beasts that were once just especially demanding passengers? No problem. There are 999,999 more of you waiting to be rehydrated. Whatever equipment you’ve gathered will be passed on to them, and they’ll continue your mission, reassured delightfully unconvincingly by a prim and proper AI that sees you as nothing more than a squishy means to its grim end that you somehow matter. You don’t. And that, strange as it sounds, is all part of the fun. This is a game that dares to imagine a future in which life is so thoroughly, pointlessly, regimented by corporate overlords, and so irredeemably hollow and miserable as a result, that the only rational response is to laugh at it. Lest you go wonderfully, beautifully insane. I’m not a reviewer with years of experience (or really a reviewer at all), and I don’t fancy myself a particularly amazing player, but I can say that, but for a few questionable moments when I was somehow shot by a gun turret despite being completely obscured from its line of fire by a wall, any instances of complaints about gameplay were virtually nonexistent. Each weapon feels unique to wield, devising tactics to either avoid or, if necessary, murder citizens (the game’s similarly lovely euphemism for those unfortunate Sargasso denizens warped into monsters by prolonged exposure to whatever is going on in the nebula) is a compelling challenge that never fails to satisfy when you succeed. The metagame, building up an arsenal of improvised weaponry, from a cobbled together pistol to a makeshift cattle prod, to my personal favorite, a medical stapler turned grotesquely lethal shotgun, is similarly rewarding, and provides a real sense of connection from client to client. It was fascinating to note how much each client came to mean to me despite how little each person matters to anything and everything in this game’s universe. At one point, I grew especially attached to a character who managed to clear a frankly absurd amount of ships using tactics so reckless there was no reason she should have lived that long. Coupled with the gameplay-altering traits the game assigns them, traits often relevant to the character’s “crime (for example, being arrested for running in a CNT facility often comes with a trait that enhances the client’s running speed),” it’s shockingly easy to anthropomorphize them in a way that makes the game that much more fun. And with that, I must say: RIP Harris; you shall forever be the giant upon whose shoulders my eventual escapee (she ended up being named “Allen;” she had a cybernetic jaw and was cool) will stand. This effect was so pronounced, I actually resented Harris’s immediate replacement, and I’m ashamed to admit I might have been a little bit glad when she finally died. Sorry, King. You didn’t do anything wrong. You just weren’t Harris. But at least I got Allen out of the deal, so your death wasn’t for nothing. Part 2: What makes this a good break for the busy?First, this game makes a narratively understandable use of an oft-maligned gameplay mechanic: timed missions. Anybody who grew up in the 90s like me probably remembers just how overused this idea was. Why did Mario only have 10 minutes to reach the flagpole, Nintendo?! Huh?! Was it going to explode? Was Wario gonna blow up the mushroom kingdom he expended all that effort to take over?! No! Stop it! It was often a crutch of false tension that just served to frustrate, especially when you reached the end of a level literally one second too late and were forced to start the entire thing from the beginning, fueling that toxic cycle of determination that compels one to complete the level because damn it, now it’s personal. But Void Bastards uses this brilliantly. You’re exploring derelict ships. They’re damaged, stripped down hulks left to drift in space. Of course there wouldn’t be any oxygen on them. And of course that would necessitate a spacesuit. And of course that means you only have so many breaths to breathe. It’s a brilliant system that not only introduces an element of strategy - it’s often advisable to plan your route around a ship so that you’ll pass through the atmo module, where what little oxygen remains aboard can be siphoned into your suit, thereby buying you precious time to grab what you need, be it fuel, food, or that form BACS is insisting you need to fill out before the Void Ark can legally be allowed to leave the nebula - but also creates a gameplay loop that completes in a reasonable amount of time. At most, your oxygen supply is going to last you 30 minutes, and that’s once you’ve really built up your equipment in the metagame. And most of the time, if you play well, you won’t need all of them. I was in and out of a ship in less than 10 minutes most of the time, having either grabbed only what I needed, or even, on occasion, utterly ransacking the vessel for every last valuable aboard. I should mention I was playing on normal difficulty; I found the more manageable difficulty less frustrating and thus more fulfilling; I’m sure many gamers can relate to a pathological hatred of losing compelling just one more run until we finally, after emotionally exhausting ourselves win, but ultimately either end our play sessions in a foul mood, which is the opposite of the point of playing a game, or press on until we win enough to satisfy our borderline insatiable pleasure centers, which is the opposite of what I want from a game nowadays. This meant that I could get the full experience of exploring a derelict spaceship full of monsters, experience this game’s masterful world-building (the ship announcements are amazing and provide so much insight into just how comically awful life in the Void Bastards universe is), and get to engage in a fulfilling metagame in 10 minutes. I could do this two or three times and still have spent a perfectly reasonable amount of time away from work, and then return to said work having had my fun and given myself a much-needed mental rest. It’s brilliant. Second, this game is not frustrating or stressful. Since death is so meaningless, aside from the aforementioned attachment, which is probably something a player can take or leave - it’s just something I enjoy doing - it’s not the sort of setback that makes me want to play until I win so I don’t leave in a huff. Death of clients is the point of the game. Seeing how far you can get is rewarding, but it’s equally funny when a string of clients drop like flies just so BACS can find itself that pen it needs. Because of this, I found the death of a client was as satisfying a stopping point as a successful raid. It didn’t matter which happened; both were narratively rewarding, because in their own way, both edge you closer to your goal. Even the horror elements are more fun than anything else because the game doesn’t go for jump scares. It goes for suspense, and in suspense lies strategy.

In true comic book fashion, citizens telegraph their movements with visual onomatopoeias, and over time, you’ll come to recognize that “STEP STEP STEP” indicates one enemy type, “STOMP” indicates another, tougher one, and “TAP TAP TAP” can indicate one of two things, forcing you to then listen to what the creature is muttering to itself to get a better sense of what you’re up against. Finally, it’s repetitive. The whole game is just: 1. Pick ship to fly to. 2. Find stuff on ship you need. Or maybe die. Then someone else can do this. 3. Bring stuff back. Or maybe die. Then you lose the stuff but there’s other stuff elsewhere. 4. Use stuff to build new stuff. 5. Repeat. Or maybe die. That’s it. And you know what? That’s amazing. It means I don’t have to worry about spending a bunch of time constantly learning new gameplay as the story progresses; I can just dive in, knowing exactly what I’m doing, raid a ship, maybe two or three more, revel in the narrative whether a client lives or dies, and then be done. As I discover games like this (and I have a lot more to come), I’m gradually coming to appreciate a game that becomes repetitive after an hour or less. Because that means I’m satisfied after that time. I’ve had my fill. I’ve had my fun. I know what I’m getting into when I play again. And now work awaits. I am, well and truly, “good.” The verdict: Aesthetically stunning, brutally funny, and just plain fun. If you’re in the market for a good sci-fi shooter that’ll test your discretion as much as your valor, this is it. For the weekdays: Up to three or so raids usually do it for me. For the weekends: Lends itself perfectly well to extended play but is often satisfying after said two or three ships. Enjoy either way; it’s amazing for both!

1 Comment

4/22/2021 06:32:06 am

This was a fun read. I loved these phrases:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Zachary JohnsonMath geek. Voice actor. Dork. If the third one paid, I'd already be rich. Archives

July 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed